The Mack

| The Mack | |

|---|---|

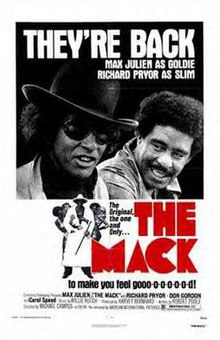

1977 theatrical re-release poster | |

| Directed by | Michael Campus |

| Written by | Robert J. Poole |

| Produced by | Harvey Bernhard |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Willie Hutch |

Production company | Harbor Productions |

| Distributed by | Cinerama Releasing Corporation |

Release date |

|

Running time | 110 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $250,000[1] |

| Box office | $3 million (rentals)[2] or $4.3 million[3] or $9,590,000[4] |

The Mack is a 1973 American blaxploitation crime drama film directed by California native Michael Campus and starring Max Julien and Richard Pryor.[5][6] The film also stars Oscar-nominee Juanita Moore and Tony-nominated actor Dick Anthony Williams. Filmed in Oakland, California, the movie follows the rise and fall of Goldie, who returns from a five-year prison sentence to find that his brother is involved in Black nationalism. Goldie decides to take an alternative path, striving to become the city's biggest pimp.

Although reviews were less than favorable when initially released, The Mack is considered by many critics to be the best entry in its genre.[7] The film is often categorized as blaxploitation, but Michael Campus,[8] Max Julien[9] and others involved in its production have argued that the genre label oversimplifies the film.

The film's soundtrack was recorded by Motown artist Willie Hutch.

Plot

[edit]After returning home from a five-year prison sentence, John "Goldie" Mickens has a plan to achieve money and power in Oakland, California, by becoming a pimp. Goldie's criminal ways contrast with his brother Olinga's Black Nationalist efforts to save the community from drugs and violence. With Slim as his partner and Lulu as his head prostitute, he organizes a team of women and quickly rises to prominence. His success catches the attention of Fat Man, the heroin kingpin that Goldie worked for before heading to prison, and Hank and Jed, two corrupt and racist white detectives. Goldie refuses to work for Fat Man again, and dismisses the detectives' requests to stop his brother from ridding the streets of drugs. As a result, his mother is assaulted which eventually leads to her death. Although Olinga is disappointed in Goldie because he "brought death to their house", he agrees to help him get revenge. They develop a plan with Slim to seek revenge, but their plans fall apart when Hank and Jed kill Slim at their rendezvous point. They reveal that they are responsible for Goldie's mother's death, causing Goldie and Olinga to kill them both. Realizing that one of his hookers, "Chico", snitched him out to Hank and Jed, he attempts to shoot her but then holds back and leaves. Oakland is now too dangerous and Goldie hugs his brother goodbye and heads out of town on a charter bus.

Cast

[edit]- Max Julien as John "Goldie" Mickens

- Richard Pryor as "Slim"

- Juanita Moore as Mrs. Mickens

- Carol Speed as "Lulu"

- Roger E. Mosley as Olinga Mickens

- Dick Anthony Williams as Tony "Pretty Tony"

- Don Gordon as Hank

- William Watson as Jed

- George Murdock as "Fatman"

- Paul Harris as Blind Man

- Kai Hernandez as Chico

- Annazette Chase as "China Doll"

- Junero Jennings as Bob "Baltimore Bob"

- Lee Duncan as Sergeant Duncan

- Sandra Brown as Diane

- Christopher Brooks as Jesus Christ

- Fritz Ford as Desk Sergeant

- Norma McClure as Big Woman

- David Mauro as David "Laughing David"

- June Wilkinson as (uncredited)

Production

[edit]Production for the film took place from early September to late December 1972.[10] According to director Michael Campus, the original script for the film was written on prison toilet paper by Bobby Poole, an inmate at San Quentin. While staying in Oakland for two months, Campus met Frank Ward, a real pimp and drug dealer from Oakland. Max Julien's character of Goldie is based on him. To shoot the movie, Campus needed Ward's permission because many scenes were filmed in his territory. In exchange for his guidance and protection, Campus put Ward in the film. All of the homeless people, junkies, pimps and women in the film were supplied by Frank Ward.[11]

Although Campus had Ward's protection, the film was also in Black Panther territory. During filming, Black Panther party members would throw bottles and trash cans from rooftops. For filming to run smoothly, an additional deal was made with Huey Newton and Bobby Seale, who were put in charge of providing extras for the film. About halfway through the production of the film, Frank Ward was shot and killed while in his Rolls-Royce. There was speculation that the Black Panthers were responsible for Ward's death, and the filmmakers and cast relocated to safer areas for filming. Despite the tension, the film's opening was shot in Oakland, with all of the proceeds going to the Black Panthers' breakfast program.[12]

Reception

[edit]The film was screened in theaters in approximately 20 mostly Black communities. Distributors avoided theaters in predominantly white neighborhoods due to a belief that the film would do better in Black areas. Despite its low distribution, director Michael Campus noted that the film outgrossed The Godfather in the cities in which it played.[5]

Alternate score

[edit]In its original 1973 release by Cinerama Releasing and its 1978 reissue by AIP, The Mack featured a score by Willie Hutch, an artist and producer for Motown Records. In 1983, Producers Distributing Corporation reissued the film to capitalize on the resurgent popularity of Richard Pryor and Roger Mosley, who was co-starring on the hit TV series Magnum P.I. PDC commissioned a new score by Alan Silvestri featuring vocals by Gene McDaniels. The reissue poster advertised a soundtrack release on Posh Boy Records, but the album was released on the ALA Enterprises label; it is now out of print and highly collectible. To differentiate it from the original score, fans have referred to it as "The Mack and His Pack," based on a catch phrase used on the reissue poster. When the film was initially licensed to Embassy Pictures for home video, it included the Silvestri score. The New Line DVD release restored the original Willie Hutch score to the film.

References in popular culture

[edit]- In a scene in the 1993 film True Romance, The Mack is playing on a TV screen in the background when Clarence Worley (played by Christian Slater) confronts Drexl Spivey (played by Gary Oldman).

- The film's theatrical poster is spoofed in the 2012 Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles fifth-season episode "The Curse of Savanti Romero".

References to soundtrack

[edit]- Dr. Dre sampled “Brother's Gonna Work It Out” in “Rat-Tat-Tat-Tat” from the album The Chronic.

- Usher sampled "Mack's Stroll/The Getaway (Chase Scene)" in "Superstar" from the album Confessions.

- Chance the Rapper sampled "Brother's Gonna Work It Out" in "Lost (ft. Noname Gypsy)."[13]

- Chief Keef also sampled "Brother's Gonna Work It Out" in "Nobody", a collaboration with Kanye West.[13]

- A$AP Mob also sampled "Brother's Gonna Work It Out" in "Put That On My Set", from their collaborative album Cozy Tapes: Vol. 1: Friends.

- UGK heavily sampled "I Choose You" in their 2007 song "International Players Anthem (I Choose You)" featuring Outkast, from the album Underground Kingz. The song peaked at number 70 on the US Billboard Hot 100. Prior to this, the song was sampled by Project Pat for his 2002 song "Choose U", from the album Layin' da Smack Down. Both "Choose U" and "International Players Anthem" were produced by DJ Paul and Juicy J from Three 6 Mafia.

References

[edit]- ^ Vincent L. Barnett (2020) Super Fly (1972), Coffy (1973) and The Mack (1973): Under- and Over-Estimating Blaxploitation Box Office, Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, 40:2, 373-388, DOI: 10.1080/01439685.2019.1697036

- ^ "Big Rental Films of 1973", Variety, 9 January 1974, p. 19.

- ^ Donahue, Suzanne Mary (1987). American film distribution : the changing marketplace. UMI Research Press. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-8357-1776-2. Please note figures are for rentals in US and Canada

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

mackwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b "'The Mack' is back after 40 years". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- ^ Dutka, Elaine (1997-06-30). "ReDiggin' the Scene". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2011-01-30.

- ^ McLevy, Alex (June 23, 2018). "The Mack remains one of blaxploitation's most artistically ambitious films". The A.V. Club. Onion, Inc. Retrieved August 24, 2019.

- ^ Walker, David; Rausch, Andrew J.; Watson, Chris (2009). Reflections on Blaxploitation: Actors and Directors Speak. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810867062.

- ^ Nix, Laura (Director) (2002). Mackin' Ain't Easy (Motion picture).

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". Catalog.afi.com. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ^ "See Why Black Panthers Got Violent With Crew On "The Mack" Movie Set". I Love Old School Music. 23 March 2015.

- ^ Walker, David; Rausch, Andrew; Watson, Chris (2009). Reflections on Blaxploitation: Actors and Directors Speak. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow. p. 19.

- ^ a b "Listen to the Willie Hutch song both Chief Keef and Chance the Rapper sampled". Chicago Reader. Sun-Times Media, LLC. 18 December 2014.

External links

[edit]- The Mack at IMDb

- The Mack at Rotten Tomatoes